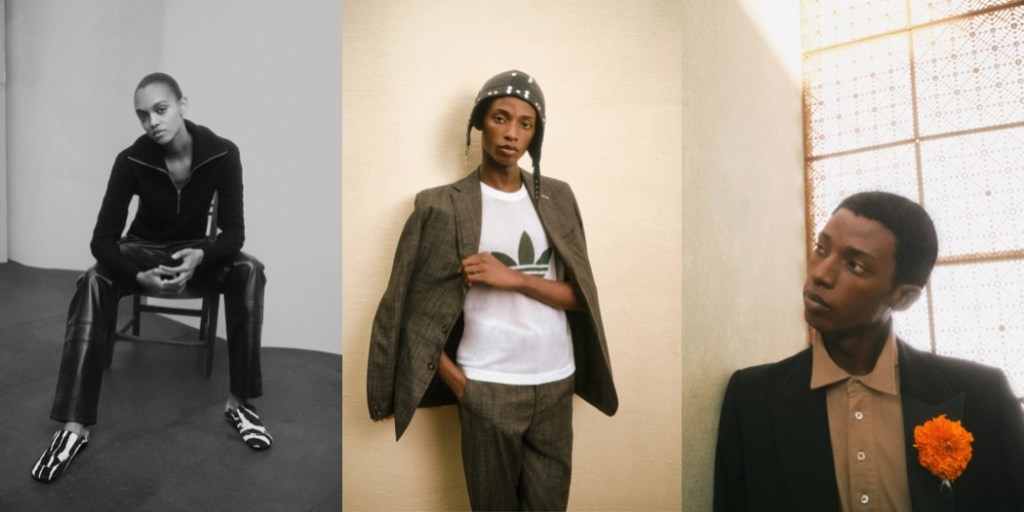

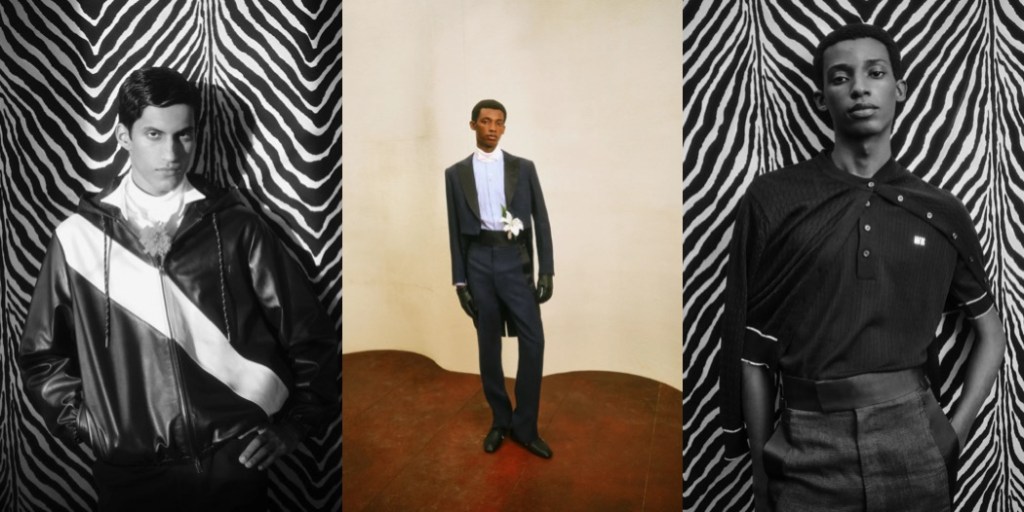

Grace Wales Bonner is one of the most convincing (and educational!) story-tellers in today’s fashion industry. Her latest collection showcased the final chapter in a trilogy, begun last January, which explores the cultural and sartorial threads that interlink Britain and the Caribbean. “This subject is the starting point for why I’m interested in creating,” said the designer, who is British born but of Jamaican heritage. “During this time I feel like I’ve really been grounding myself in this framework, and refining myself within it. These collections are about consolidating and reinforcing what is timeless to me; representing the breadth of what Wales Bonner is, and can be.” Thus far in the series the designer has looked to the second-generation Jamaicans who established London’s 1970s Lovers Rock scene to inform her designs, and then the dress of Jamaica’s dancehall and reggae stars. Here she started by exploring the wardrobes of Britain’s Black scholars in the 1980s: those who traveled from across the world to study at the likes of Oxford and Cambridge. There was a reimagining of their academic attire – of tweed blazers and knitted scarves, well-worn chinos and striped jumpers – but within that historicism, “I was thinking about how in certain spaces people create a language for themselves,” reflected the designer. “About how you might disrupt an institution from inside.” It’s a subject that has long fascinated Wales Bonner, whose brand was established with the intention of disrupting the luxury perspective, redirecting it from its often singular focus on Eurocentricity. So poets like the Barbadian Kamau Brathwaite and the Saint Lucian Derek Walcott appeared as more than just aesthetic character studies; rather, they were catalysts for considering a post-colonial movement that explored “what it is to be in another place, or from another place.” The resonant words of Braithwaite, who left Bridgetown to study at the University of Cambridge, were spoken over the immersive film directed by Jeano Edwards which accompanied the collection: “You had not come to England / You were home.” In terms of clothing, Wales Bonner imagined what she termed the wardrobe of the “outsider intellectual,” considering the structure of British traditions and wondering “within that framework, how do you create something new?” She found her answer by imbuing her distinct take on sartorial eclecticism with a gently liberated, multicultural sensibility. The designer worked with Savile Row tailors at Anderson & Sheppard on tuxedo suiting inflected with Afro-Atlantic flair and elsewhere she softened Oxford shirting, printing cotton cashmere with Jamaican “flowers of resistance” from the photograms of artist Joy Gregory. Boating striped overshirts simultaneously channeled Oxbridge classicism and West African dashikis; brushed denim was cut into crisp suits. A sense of ease was injected into even the most traditional tailoring. Woodblock prints and Indian embroidery drew on the diasporic nature of her research, and a deliberate diversity was instilled throughout. “What I was trying to connect with is a sense of expansiveness and possibility,” said Wales Bonner. “For example, in Derek Walcott’s The Gulf, he has a poem about different Indian gods. You think you’re looking at Caribbean thought, but then there are all these other influences. Once you start researching anything, you realize that nothing is simple. Nothing is one thing. So I didn’t want to make anything too neat.” That expansive notion was echoed, too, in the latest iteration of Wales Bonner’s Adidas collaboration – a partnership that has recently taken fashion by storm. “I was trying to imagine a fictional university that is a lot more multicultural,” she said of its new evolution. “Maybe what their team kits for a track program might look like.” Referring to “the origins of sportswear – when it was made in a beautiful, crafty way which feels almost tailored,” Wales Bonner leaned into Adidas’ technical resources to revive specific fabrications like ’60s jerseys and lived-in wools “to make things feel authentic,” she said. A T-shirt printed with the emblem for “Wales Bonner Adidas Originals Literary Academy” offered a tongue-in-cheek nod to the extensive footnotes which typically accompany each of the designer’s collections. But what has been proven by the sell-out success of her tracksuits and trainers is that, even without related reading, there is something uniquely compelling about Wales Bonner’s designs: the heavy-duty weight of her research injects something intangibly compelling into her clothes.

Collage by Edward Kanarecki.