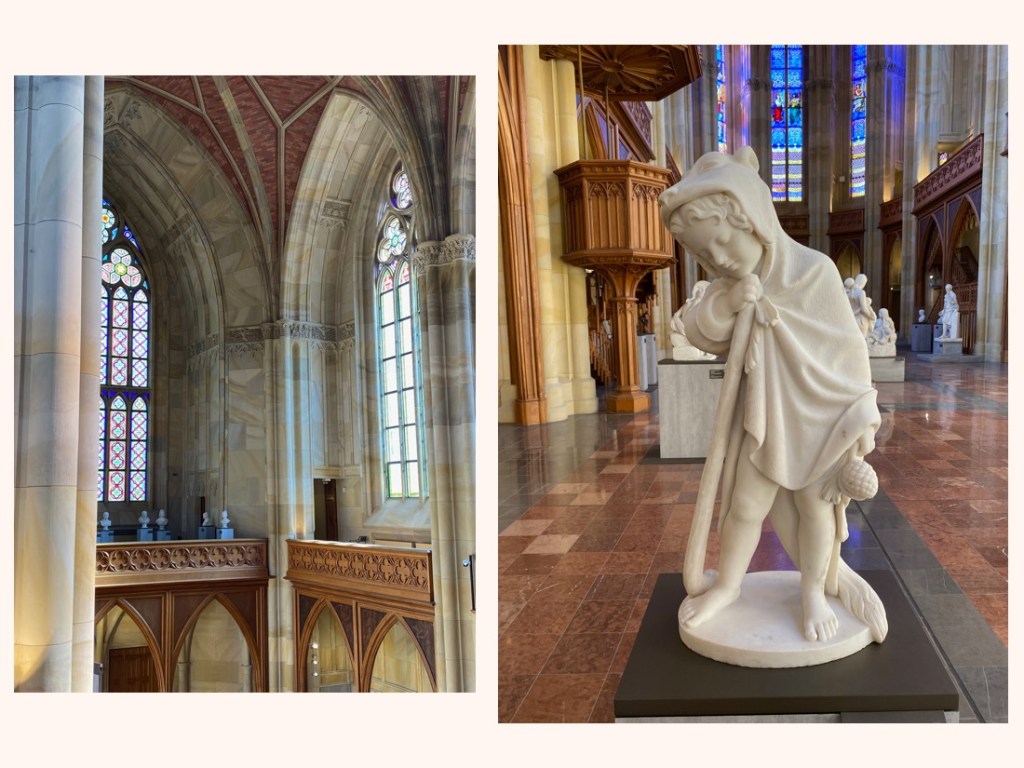

In Berlin, I stumbled upon another sort of sci-fi scenario. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe once adoringly described Luise and Friederike, the Mecklenburg-Strelitz sisters as “heavenly visions, whose impression upon me will never be effaced”. Sculptor Johann Gottfried Schadow erected a monument to their elegance and grace, creating an icon of European classicism with his double sculpted portrait of the “Crown Princess Luise of Prussia and her Sister Princess Friederike of Mecklenburg-Strelitz”. The statue of these two figures, which has come to be known under the abbreviated title Princess Group, is one of the highlights of the Alte Nationalgalerie’s collection. Now, the sculpture is back on permanent display at the breathtaking Friedrichswerdersche Kirche. The original plaster cast has a particular significance within both the broader context of Schadow’s oeuvre and that of 19th-century sculpture: it is here that not only the artist’s creative signature is at its most palpable, but also the thrilling genesis of the double-figure statue.

Showcasing sculpture from Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s era through to the German Empire, the exhibition “Ideal and Form” at Friedrichswerdersche Kirche traces the medium’s lines of development through the long 19th century into the modern era. It also invites visitors to rediscover the Berlin School of sculpture, a movement whose international outlook was ahead of its time. With more than 50 sculptures – some monumental in scale – this exhibition provides a comprehensive survey of the work of the Berlin School and of its complex international ties. On display are major works by Johann Gottfried, Emil Wolff and Christian Daniel Rauch, and by female sculptors such as Angelica Facius, Elisabet Ney and Anna von Kahle.

Werderscher Markt / Berlin

All photos by Edward Kanarecki.

Don’t forget to follow Design & Culture by Ed on Instagram! By the way, did you know that I’ve started a newsletter called Ed’s Dispatch? Click here to subscribe!